Burma’s 1 million Rohingya Muslims are the long-standing victims of the Burmese military regime. They have been horribly hit by the cyclone several years ago.

Today they are being massacred–more fruits of democracy in Mayanmar!

Burma is strategically extremely very important to Pakistan. China uses two of its ports as part of its “string of pearls strategy” which extends from Gwador to Hainan in China. Gwador is a sister port of Sittwe, Coco and Zadatkyi.

Pakistan should participate in the cyclone relief in a big way, and take the Arab and Islamic countries with them.

- Moorish Marronage Muslims of Jamaica

- Linguistic heritage of Pre-Columbus Muslims

- Cherokee Muslims in the USA before Columbus

- Current day Muslims in Germany

Muslims brought about the renaissance in Spain 3 centuries before Italy

Burmese Muslims a forgotten minority

Thai Occupied Muslim Sultanate of Patani”

- Mayanmar’s Rohingya Muslim population, an isolated group in Northern Rakhine State (NRS), remains oppressed by Burma’s rulers and depends on international donors for survival.

- The estimated 728,000 community members live as virtual prisoners as a

- The government’s long-standing campaign to “Burmanize” the population even has included the coerced conversion of Rohingya Muslims to Buddhism.

- Despite having a presence in the area extending back to the seventh century, the Rohingyas are not considered to be Burmese citizens and they suffer legal, economic and social discrimination.

- They face severe restrictions when attempting to travel, engage in economic activity, register the births, deaths and marriages in the community, and obtain an education.

- Since the 1970s, the government has made it very difficult for the Muslims to practice their faith, restricting and sometimes banning the publication and distribution of the Quran, and effectively limiting participation in the hajj through restrictive passport and visa issuance procedures.

- The government also has targeted Muslim places of worship, ordering mosques to be closed down or even destroyed.

ROHINGYA REFUGEES

- As a result of the regime’s abuses, a large number of Rohingyas have become international refugees. Many make up part of the approximately 1 million illegal Burmese migrants in Thailand.

- The Rohingyas’ most popular destination has been neighboring Bangladesh, but between 1991 and 1992, the government in Bangladesh forcibly repatriated 250,000 refugees, citing overpopulation and land scarcity in the country. UNHCR also has documented 12,000 Rohingya refugees in Malaysia, but has conceded there might be twice that number actually there.

- In addition, an estimated 500,000 internally displaced Rohingyas have been forced from their lands by the Burmese government, leaving many, especially women and children, vulnerable to human trafficking.

English:

Sunday textile market on the sidewalks of Karachi, Pakistan. Français :

Marché au tissus du dimanche sur les trottoirs de Karachi, au Pakistan.

Canon EOS Digital Rebel / 18-55mm Canon lens (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Pakistan Tablighi Jamaat was busy influencing the Rohingya of western Burma.

- It was here in the warrens of Karachi’s underbelly that the Rohingya founded a settlement after fleeing persecution by the Tatmadaw (the Burmese military). The Rohingya, after suffering acute religious persecution, were a perfect fit for the Tablighi’s proselytizing.

- Aziz’s neighborhood also houses thousands of stranded Bangladeshis who presence in Karachi pre-dates Bangladesh‘s 1971 linguistic-based liberation war from Pakistan. These quasi-indigenous Bangladeshis have then been joined by more recent Bengali migrants seeking wider job opportunities and a chance to earn a stronger currency. Aziz informed me that the missionaries from Tablighi Jamaat were quite active in Korangi. They were also hugely influential in Bangladesh where the group hosted the world’s second largest yearly Islamic pilgrimage after the Hajj.

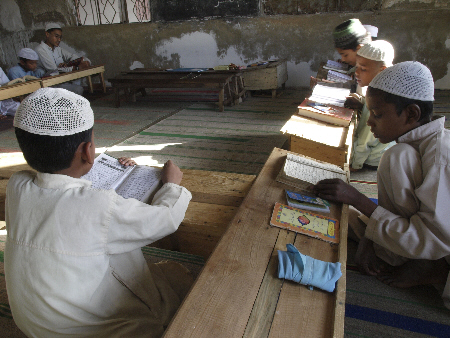

Rohingya children studying the Qu’ran at the Madrassa Usmani in Karachi.

- The Tatmadaw had come to his farm some twenty years ago and claimed they were doing a census on behalf of the junta. Since Saraj was one of Arakan’s land owning Muslims, the soldiers burned his crops, confiscated his land and told him in no uncertain terms that he must leave Burma with his family because the Burmese are a Buddhist people and he “must have come from somewhere else” implying he was of South Asian origin. At first he fled to southern Bangladesh and lived in a majority Bengali village where other refugees had temporarily made their homes. It was not long before the Bangladeshi authorities told him and his family that they were not welcome there either. Like many Burmese fleeing Arakan state, Saraj did not arrive in a large, visible exodus.

- He and thousands of his countrymen arrived in a quiet yet constant trickle across the Naf river. It was at this point that he and many of the Rohingya in Pakistan morphed from being destitute refugees displaced by the Tatmadaw’s brutal coercion into actual economic and religious migrants seeking work in Pakistan.

A Rohingya boy hawks vegetables in a Bangladeshi bazaar in Karachi.

Saraj told me that missionary Pakistani members of Tablighi Jammat

had convinced him that Pakistan would much more suit his tastes. Saraj,

who stated that he was around 85 years old, said he would return to

Burma immediately if he could have his land back and was allowed to

openly practice his religion.

Rohingya migrants posing in front of a garment shop.

- In the twisted realm of South Asian proxy politics, India has accused Bangladesh and Pakistan’s intelligence services of supporting insurgent groups such as the United Liberation Front of Asom and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland who are fighting against Indian rule.

- In turn, these groups have taken periodic shelter in western Burmaafter allegedly being trained in militant camps in Bangladesh. It is quite common practice in South Asiafor rival governments to aid in agitating ethnic grievances in the other’s territory in order to keep their opponents off balance.

- The Rohingya, while once being left to fester during the Sino-Indian rivalry that followed China‘s invasion of India in 1962, are now an absolute lost cause in the noise of this new competition. The economic tentacles of these emerging powers are furiously grasping for influence inside both Burma and Bangladesh.

- Over the decades since the Sino-Indian confrontation, China supplied arms to anti-Indian war fighting groups in Burma, Bhutan and Bangladesh when irritating Delhi suited Beijing‘s aims of the day. China also supplied arms to both the Burmese junta and ethnic guerillas fighting the junta depending on the politburo’s mood swings. War by proxy is politics as usual in the region, and Burma exists in its most dim corner.

- After hearing first hand accounts of hijira from the Rohingya elders, Aziz and I then visited a bare-walled, local Burmese religious school called Madrassa Usmani. There, I met a group of Pakistani-born Burmese children who were rocking back and forth studying the Qu’ran on a fraying sun bleached carpet. A young maulvi (religious instructor) named Abdullah told me that the people of his generation witnessed mass destruction of their religious institutions by the junta as they were being forced out of their once home country.

- In Pakistan, it was the Islamic charities who provided aid and “proper” religious instruction for the children of the community as per the standards of Pakistani society. It is from just this milieu where students can be cultivated into fighters. I left with only the hope that these vulnerable, young Rohingya would not fall for the siren song of violent radicalism gripping much of modern Pakistan. As we have learned the hard lessons from the militancy spawned in Pakistan’s notorious Afghan refugee camps, it is not terribly difficult for yesterday’s victims to become tomorrow’s aggressors.

Market scene in Bangla Para, Karachi.

I explained to my driver that I didn’t have quite enough material

for a story and that we needed to delve deeper into the area. He said it

wouldn’t be safe to proceed any further without the guidance of his

brother. Aziz’s brother, it turned out, was an MQM operative. The MQM,

which stands for the Muttahida Quami Movement, is Karachi’s dominant

political force and sometime terrorist outfit. The MQM controls large

swathes of this 15 million strong port city with a mix of intimidation

and sheer brut force. From the comfort of our air-conditioned sedan, we

followed Aziz’s brother on his motorbike through alleys strewn with

burning rubbish flooding with humanity until we reached an area called

Bangla Para (literally “Bangladeshi Area”).

When we arrived, our car was immediately surrounded by curious

Bangladeshis who looked particularly at me with a great deal of

suspicion. I followed the MQM man deeper on foot into the bazaar

capturing its life on camera while also inquiring about its inhabitants

ethnic identity, a naturally sensitive subject in an area full of

illegal migrants living outside the mainstream of Pakistani society.

I essentially had the MQM man ask groups of men and boys which

languages they spoke and went from there. Many of the Rohingya had come

to Karachi hoping they could find work in the fishing industry as they

had done in Arakan. The irony of them fleeing Bangladeshis

that they seemed to be naturally drawn to settle amongst Karachi’s

Bengali community. Here they could attempt to blend in with the Bengalis

with their colorful lungis and white skull-caps. The people of southern

Bangladesh spoke a dialect known as Chittagonian that is somewhat

mutually intelligible with the Rohingya’s language. Since both groups

had essentially fled conditions in Bangladesh (albeit for very different

reasons), they also shared the same arduous migration as recent common

history.

As we drove away from the rough neighborhood these former refugees

now call home, I naively said to my driver, “I actually felt pretty safe

there.” Aziz looked at me skeptically and said in his heavy Pakistani

accent, “that is the most dangerous area of Karachi.” Considering

Karachi is one of the world’s most violent cities, I would shudder the

next day when I read in the nation’s leading English-language daily that

five men had been shot dead in Korangi during my brief visit.

As we drove out of the crowded slum into the overwhelming traffic

of Karachi proper, I thought it a strange fate that the Rohingya fled an

area where they faced state orchestrated violence only to arrive in

another area plagued with rampant crime and anti-state and sectarian

terrorism. Karachi may have its dreadful shortcomings but at least here

in their relative anonymity, the Rohingya are free. While in India the call centers buzz, and in China the factories hum, in Burma, the generals keep marching. The Worlds of Islam: The Inquisition against Muslims

The Muslim JesusMuslim “Darwin” to Islamic “Newton”

Source: Here

No comments:

Post a Comment